Why balancing is the key to stable production

Unstable production despite correct cycle time

Many assembly lines are formally considered to be “in cycle” and yet fail to meet their stability targets. The planned number of units is only achieved with additional effort. Jumpers are regularly deployed, rework occurs outside the line and minor disruptions escalate quickly.

The cycle time describes how long a product is in a station. It therefore defines a fixed time frame for assembly. However, the fact that this framework is often not adhered to in everyday life is not due to the cycle time itself. The decisive factor is how the actual load is distributed within this framework.

Typical symptoms can be seen in practice. Individual workstations are regularly overloaded while others wait. Small deviations have an immediate effect on the line flow. The line remains mathematically on schedule, but can only be controlled to a limited extent in everyday life.

The response to this situation is often operational. Support is organized, line stoppages are accepted, tasks are relocated or reworked. These measures stabilize the situation in the short term, but increase the organizational effort in the long term. The actual cause remains, as it does not lie in the cycle time.

The central error in thinking is widespread: A “correct” cycle time is equated with stable production. In reality, the cycle time is merely the framework condition. Whether a line runs stably is determined by whether the cycle time within this framework matches the actual load.

What balancing means in technical terms

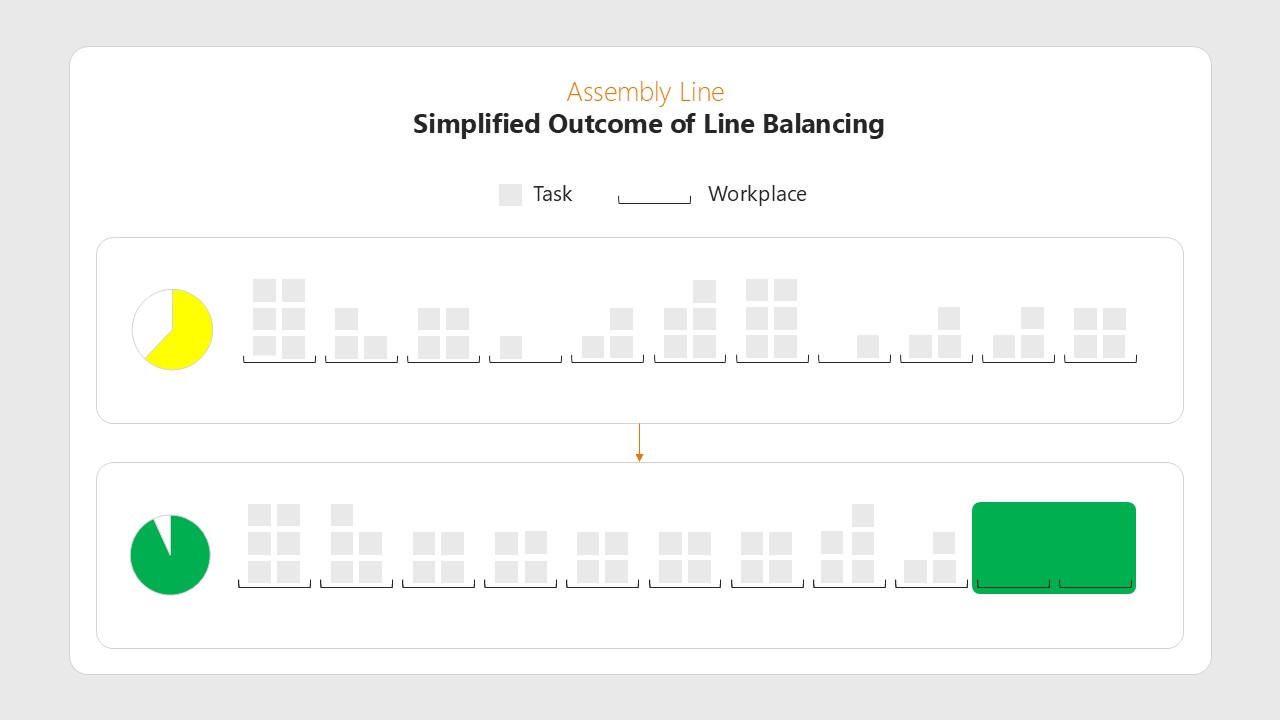

Clocking describes the systematic assignment of work processes to workstations along a line. In essence, it is not about speed, but about structure. The central question is: Which work is performed by which workstation and under what conditions? Only this assignment determines how resilient a line is in everyday use.

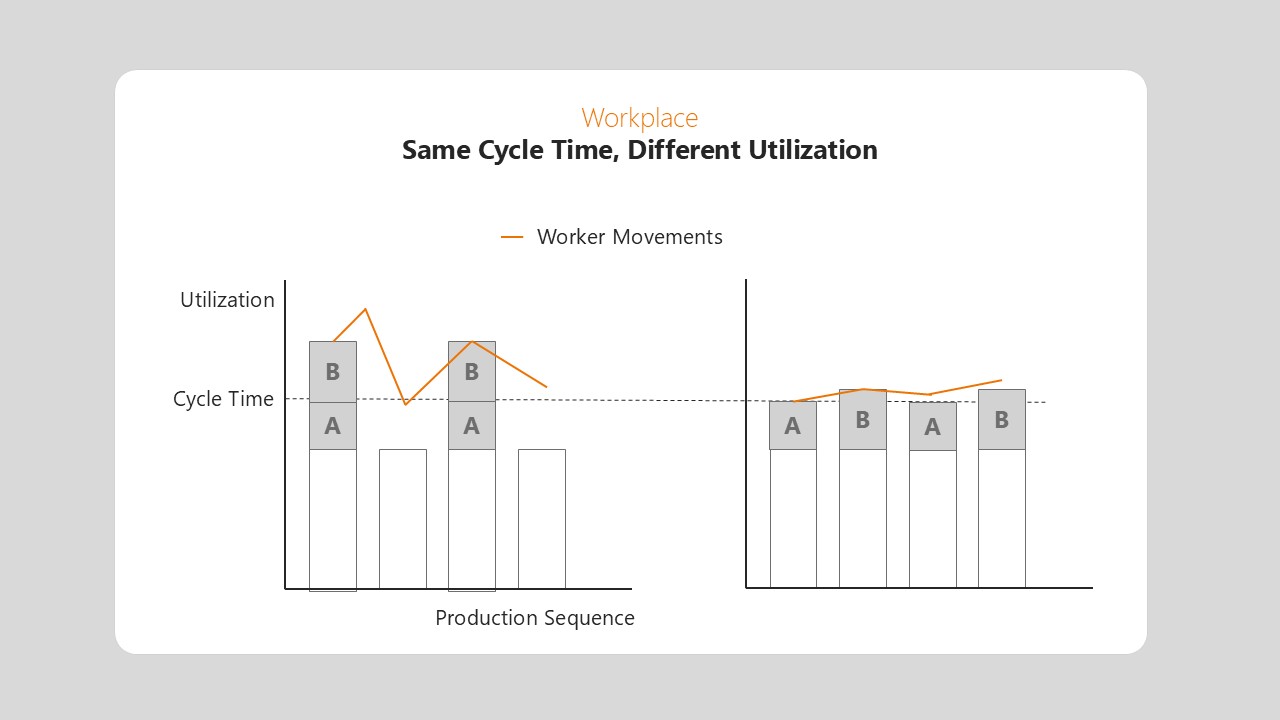

It is important to make a clear distinction from the cycle time. The cycle time defines the time frame per station. The clocking determines how this framework is used. Two lines with identical cycle times can therefore run completely differently. The difference arises from the distribution of the work content, not from the amount of takt time.

Several functional elements are part of the balancing. Work processes are assigned to work centers. Requirements such as tools, work positions or qualifications must be taken into account. At the same time, restrictions must be observed, such as fixed sequences, ties or spacing rules. Variants and their frequencies are also included in the evaluation.

This structure results in measurable effects. Utilization describes how busy a workstation is on average. The time spread shows the fluctuation in processing times per order. Bottlenecks occur where these fluctuations regularly exceed the available capacity. Without proper balancing, these effects remain hidden or only become visible during operation.

A common misconception is that balancing is a one-off planning task. In practice, the product mix, installation rates and work content change regularly. Each of these changes shifts the load along the line. Therefore, line balancing is not a static plan, but a recurring planning process that continuously adapts the structure to reality.

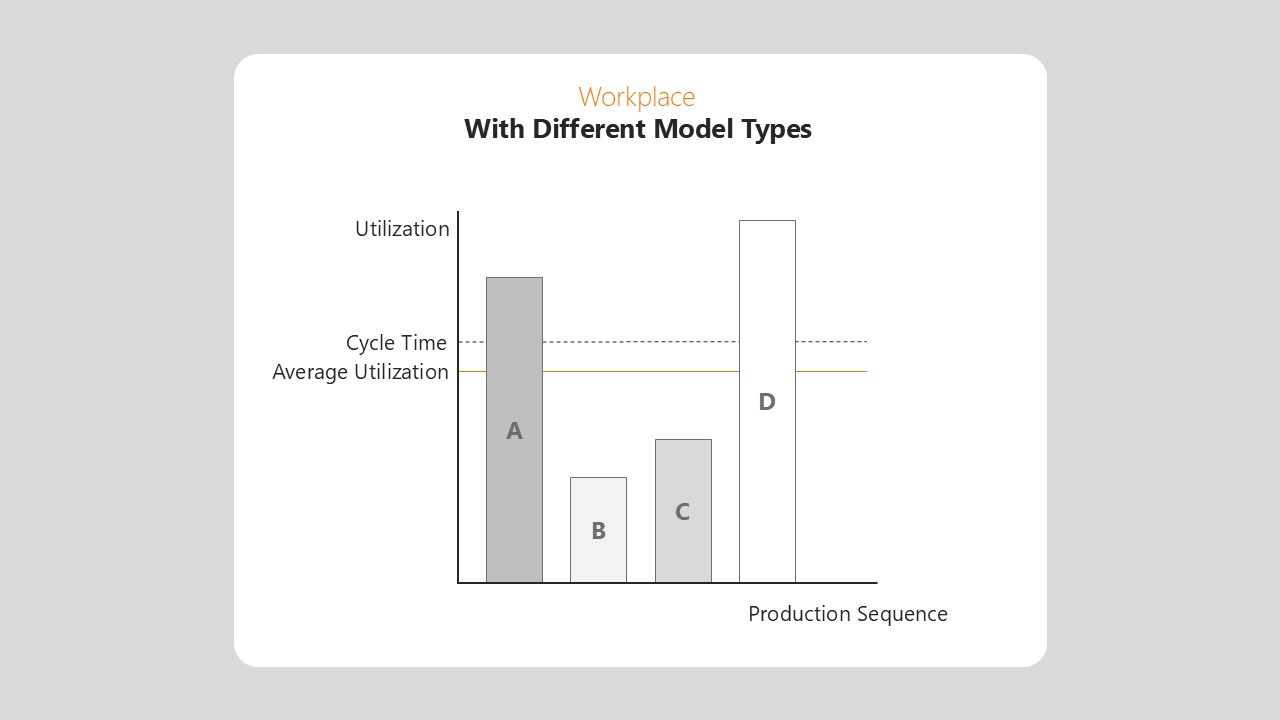

Variant mix as the actual load driver

In multi-variant assembly, stability is rarely determined by average values. The decisive factor is how strongly the processing times per order fluctuate. The mix of variants acts as the actual load driver. If individual variants require significantly more time than others, overload situations arise – even if the average utilization is below the cycle time.

Variants are often averaged in planning. This approach is mathematically correct, but ignores the reality in operation. Orders are not distributed evenly, but in specific sequences. If several time-intensive variants arrive at the same workstation in quick succession, the time frame is no longer sufficient. The result is overclocking time, which continues along the line.

Time spread describes precisely this effect. It shows how widely the actual processing times of individual orders vary around the average. The greater the spread, the higher the risk of instability. Rare variants with high time requirements are particularly critical. They hardly carry any weight in average considerations, but generate a disproportionate burden in everyday life.

Proper balancing makes these effects visible. It takes into account not only the average workload, but also the entire distribution of processing times across all variants. This allows work processes to be allocated in such a way that peak loads are cushioned. The aim is not to force every variant under the cycle time, but to make short-term ones plannable and controllable.

Without this structural approach, the line inevitably reacts operationally. Support is deployed where it is needed. In the long term, this leads to higher personnel requirements, reduced planning reliability and line stoppages. The variant mix remains the dominant disruptive factor – not because it exists, but because it was not sufficiently taken into account in the scheduling.

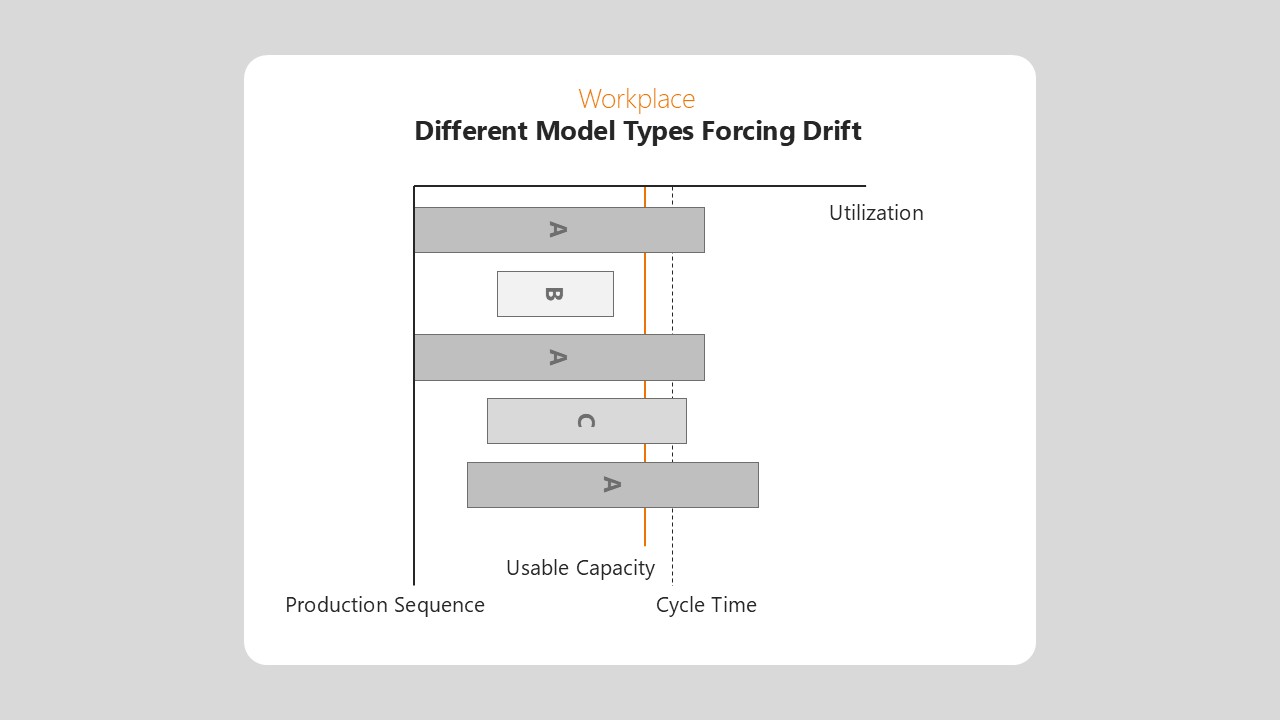

Drift as a visible symptom of unstable clocking

Drift always occurs when an order cannot be completed within the scheduled cycle time. In a continuously flowing line, drift is not an abstract time phenomenon but is directly visible. Temporal drift and physical drift are not separate effects, but two perspectives on the same problem. The time delay of an order corresponds exactly to the position of the worker or the workpiece inside or outside the station.

If a workstation is overloaded, the work shifts along the line. The worker stays longer at the product or follows it to the downstream area. This automatically delays the start of the next job. In a flow line with a continuous cycle, time and location are inextricably linked. Drift always manifests itself as a spatial shift and at the same time as a time delay.

The cause rarely lies in the individual work process. The decisive factor is the structural design of the balancing. If work content is distributed in such a way that certain variants regularly exceed the available capacity, drift occurs. This drift is not negative per se, but an unavoidable and, in many cases, useful tool in variant-rich assembly.

Drift only becomes critical when it is not consciously planned for and evaluated. In practice, drift is often tacitly accepted without using it structurally. Support is organized, workers “pull along” and the line appears to continue running. In reality, the organizational effort increases, while transparency about the actual workload is lost. Drift then does not have a stabilizing effect, but conceals structural imbalances.

When planned and handled correctly, drift enables efficient balancing in mixed-model lines. It allows variants with higher time requirements to be integrated without having to design the entire line for the worst case scenario. However, the prerequisite for this is that drift is specifically limited, evaluated and taken into account in the line balancing. Only then does it contribute to the stability and efficiency of production.

„Drift is not a special case and not a fault, but the logical consequence of clocking out in multi-variant assembly. In a flow line, overload always occurs simultaneously in time and space. The decisive factor is not to avoid drift, but to consciously plan for it, limit it and use it as a structural instrument for the design of the line. “

A stable line is characterized by the fact that drift is consciously planned, made transparent and specifically limited. The aim of line balancing is not to avoid any overload, but to design drift as a structural instrument in such a way that production stability and efficiency are achieved together in the variant mix.

Balancing as a continuous planning task

Balancing is not a one-off planning step, but an ongoing process. The product mix, installation rates and work content change regularly. Each of these changes shifts the load along the line. If the balancing remains unchanged, production gradually loses stability – often unnoticed until operational measures become the norm.

This effect is clearly evident in practice. New variants are integrated, existing work processes are adapted or sequences are changed. The cycle time remains constant, but the internal structure does not. Structural imbalances arise if the work allocation is not checked again.

This manifests itself not only in overload, but also in underutilization of individual workstations. Both have a negative impact on efficiency. The line does not react to this with fine-tuned structural adjustments, but either with line stops and loss of production – or by tacitly accepting inefficient capacity utilization.

Continuous balancing creates transparency about these shifts. It makes visible how changes in the order program affect capacity utilization, time spread and drift. This makes planning forward-looking again. Problems are recognized before they escalate during operation. Stability is not created through reaction, but through structural adaptation.

In the long term, balancing thus becomes a management tool. It combines planning and operations, makes workloads explainable and decisions comprehensible. The cycle time remains the fixed framework. However, the stability of production comes from the continuous maintenance of the work structure within this framework.

Frequently asked questions about production planning

The cycle time is the time that a product spends at each station. In assembly systems with a continuous flow, it is determined by the speed of the conveyor system. In systems with manual transfer, the transition to the next station takes place after the cycle time has elapsed.

Clocking describes how work processes are distributed to workstations and stations in order to keep to the available time. It determines which work is to be performed at which workstation within the cycle time. Only a balancing that matches the actual variant and load situation enables stable operation within the cycle time.

If work content does not match the actual variant load, regular overload situations arise. These cannot be finely balanced out during operation. This results in line stoppages and a loss of parts, even though the cycle time was calculated correctly.

The mix of variants determines the spread of processing times per order. Rare, time-intensive variants generate peak loads that remain invisible in average considerations. Proper balancing explicitly takes these effects into account and makes them manageable.

No. Product changes, new variants or changed assembly rates shift the load along the line. Balancing must be regularly checked and adjusted to ensure long-term production stability.

Stable clocking means that overload remains predictable and does not escalate. Drift occurs in a controlled manner or is limited. Belt stops and unplanned support become the exception, not the rule.